How to design a BJJ curriculum

Today’s question: how do you build a BJJ curriculum that allows you to evolve over the long-term, and what can the trade-off between interleaving and blocking teach us about it?

There’s plenty of debate about what a single BJJ training session should look like. Almost no one talks about what training should look like over months, years, or decades.

Warren Buffett has a line about investing: people overestimate what they can do in one year, and underestimate what they can do in ten.

Training BJJ is the same. When you zoom out, you see that most progress comes from small improvements that compound. And compounding only works if you give it the one variable it needs: time.

Short-term thinking breaks that. If you optimise for the next session or chase the latest trend that promises a black belt in two years, you interrupt the very process that creates long-term gains. You keep resetting the clock.

The strange thing is how hard it is to think this way. Our brains default to the next week, not the next decade. But if you can shift your time horizon, even slightly, you unlock the kind of progress that only looks slow until, suddenly, it isn’t.

Part one: Skills, time and memory

Designing a long-term jiu-jitsu curriculum is hard because you’re juggling three variables that don’t fit together.

Skills. These are effectively infinite. There are more techniques than you could ever learn, and new ones appear all the time.

Memory. This is finite. Think of it as RAM on a computer. You only have so much capacity, and the brain frees up space the same way a computer does: by forgetting.

Time. This is the force that teaches you and the force that erases what you learn. If you don’t reinforce a lesson, time dissolves it.

When you put these together, the problem becomes clear: you want to learn as many useful skills as possible, but your memory and your time horizon limit how much you can keep.

Why plan further at all?

Planning ahead prevents big gaps from forming in your game. If you’re a coach, it ensures your students are exposed to the full surface area of jiu-jitsu. If you’re training on your own, it gives you a roadmap so you don’t just drift toward the positions you already like.

Short-term training creates blind spots. Long-term planning closes them, whether you’re running a whole class or just coaching yourself.

This is why the word curriculum is useful. It sounds school-like, but it comes from the Latin currere: “to run a course.” That’s all a curriculum really is: a path. And you want to make sure the one you follow leads to a well-rounded jiu-jitsu game.

There are two main approaches people talk about when they discuss how to learn anything

1. Blocking

You take one skill and repeat it until you feel you’ve got it. Then you move on.

2. Interleaving

You cycle between different skills in the same time frame, never staying with one for too long.

In jiu-jitsu, these “skills” usually map to positions. One month, you focus on closed guard. The next is the headquarters passing. Then side control escapes. And so on.

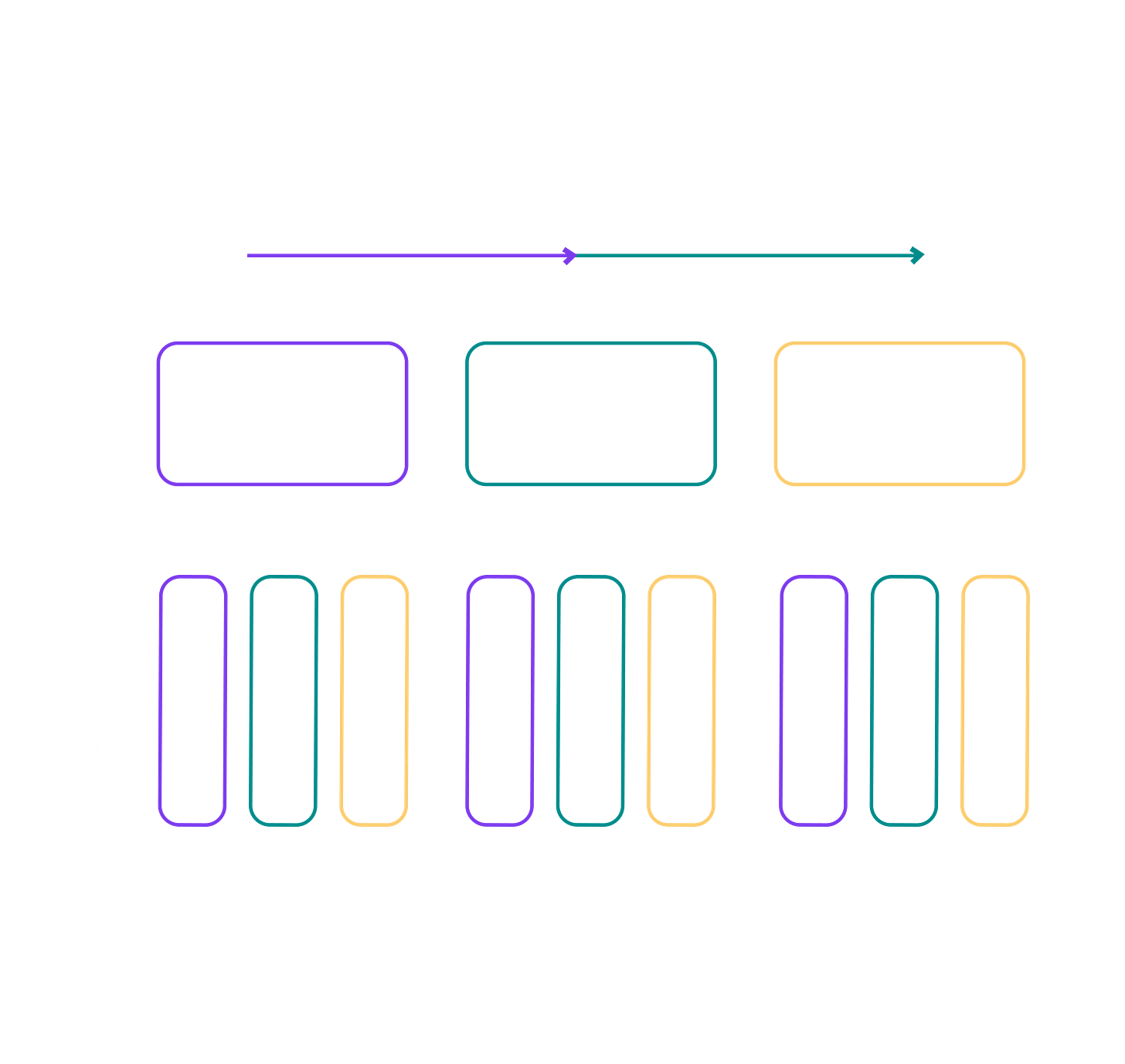

If you plotted a nine-week training plan, blocking would look like three solid chunks: three weeks on one position, three on another, three on a third.

Interleaving would slice the same nine weeks differently: you’d switch positions each week, rotating through them rather than living in one for a long stretch.

Blocking feels more comfortable because you get short-term fluency and depth in one position. Interleaving feels chaotic because you’re always being pulled out of your comfort zone. But that discomfort is often where the deeper learning comes from.

Here’s the trade-off

Before we go any further, I’m not prescribing either blocking or interleaving as the “right” way to train. But looking at the pros and cons of each tells us a lot about the trade-offs we face when building a training curriculum over time.

Blocking gives you better short-term performance, but worse long-term retention.

If you spend a month on headquarters passing, your students will look great by the end of that month. Their timing will be sharp, their reps smooth, their confidence high.

But zoom out. Once you move on to the next block, it might be months before they touch headquarters again. By then, most of that fluency has evaporated. Blocking creates spikes of progress that fade as soon as attention shifts or the context changes.

Interleaving is the opposite. It gives you worse performance in the moment, but stronger retention and transfer over time.

If one week is guard passing, the next is side control attacks, and the next is guard retention, students will look worse in each of those weeks.

They’re constantly being pulled between contexts, so nothing feels “mastered.” But over the long term, they return to each topic more frequently. The spacing helps students retain and reinforce what they’ve learnt and begin to identify patterns across positions.

Imagine your brain as a computer. Like I said before, techniques live in RAM: fast, limited, easily wiped. Principles live on the hard drive, slower to build and understand, but harder to erase.

According to the research, interleaving helps shift the important stuff from RAM into long-term storage.

The current research

The pattern in other sports

Most of the research comparing “do one thing at a time” vs “mix different things together” comes from sports like baseball and badminton. And the pattern is surprisingly consistent. In those studies, players who interleaved different skills in practice usually performed worse during training, but better in later game-like tests than players who trained in blocks.

When things get messy

When researchers looked specifically at sports skills in more open, unpredictable sports, they found some support for an interleaving approach, especially since the constant context switching is closer to real sport.

At the same time, recent meta-analyses warn against overselling it: in real applied sport settings, the advantage of interleaving is smaller and not guaranteed.

In combat sports

Right now, there isn’t a clean study comparing one group that trains in blocks and another that mixes them. But BJJ is an open, unpredictable sport where everything changes fast, more like facing different pitches than practising off a tee.

So the logic aligns with the research: mixing feels worse in the moment, but tends to build skills that hold up better when things get chaotic. There are coaches like Darragh O’Conaill who’ve talked openly about the benefits they’ve seen from using an interleaving approach with their students.

A case for blocking in BJJ

One of the tricky things about teaching jiu-jitsu is that no room is ever the same. I’ve taught in gyms across the country, and I’ve never walked into a class where everyone was at the same stage. That alone makes prescribing a single “best” method impossible.

Less experienced students

For people brand-new to BJJ, blocking helps. Staying in one position for a while gives them something solid to hold onto. It slows things down. It gives them structure before the chaos begins. In the early stages, that scaffolding matters.

Right now, I’m at a gym where no one has ever trained in heel hooks. In a case like that, a blocked approach makes sense. You need time to build the basics: how to move safely in leg-lock positions, which key positions to use, and how to avoid hurting each other. That foundation matters.

More experienced students

But as students get better, the balance changes. If you stay in one position too long, you hit the point of diminishing returns very quickly. Advanced students need more exposure to different positions. After a certain level, the problem isn’t depth but variety.

Depth vs breadth

I say that because in my experience, novice students and intermediate and above need different things:

Novices need knowledge: When you know nothing, slowing things down and staying in one position gives you a foundation to stand on. Depth matters here, so blocking makes sense.

Intermediate and above need decision-making: Their real challenge isn’t remembering techniques; it’s making the right choice under pressure. Variety helps these students step back and see the logic that connects positions, and start understanding how to transition between them.

That’s why I’ve started shifting my own approach. We’ve looked at what the research says and the trade-off it keeps pointing to. What comes next is what I’ve seen myself, and why I’ve moved from mostly blocking to trying something closer to interleaving with my intermediate and advanced students.

Part 2: Why interleaving is a strong approach for BJJ

A round of jiu-jitsu contains an absurd amount of change. Subtle shifts in your opponent’s body positioning can completely change your offensive and defensive options. This means new problems appear every second, and you need to adapt to them just as quickly.

This is exactly why interleaving works.

When you mix topics, you’re constantly being dropped into new situations. In learning terms, you learn how to context switch. In plain English, this means you have the ability to make decisions quickly when things change.

You also strengthen pattern recognition: simply noticing the same shapes and problems appearing across different positions.

Discrimination learning - knowing what is actually happening, and what you should do about it

Interleaving builds discrimination learning. In plain English, this is the ability to tell similar situations apart so you can pick the best response. It’s the moment in a roll where your brain says:

“Ah - this is happening, not that. So I should do this, not that.”

That skill shows up everywhere:

How the alignment between someone’s head and hips reveals where their weight is

How a particular frame is blocking you, and how you can move around it

How a certain attack, or defence, works on one plane (angle), and not another

This is what most intermediate students actually struggle with. Not technique shortage, but the timing and recognition that tell you when to use the techniques you already know.

I’d take this a step further and say that the difference between average and elite competitors isn’t the techniques they know, but the speed at which they can make decisions.

Where blocked practice falls short for those working on decision-making in BJJ

1. It hides the principles that make techniques work

If you spend a month on closed guard, students learn the usual list: hip bump, scissor sweep, cross-collar choke, etc. But because the context never changes, the brain tags these techniques as “closed guard things.”

The principle underneath, like posture control, becomes more challenging to identify. Students memorise moves within a specific context, rather than understanding what makes them work.

2. It prevents positions from connecting

When all training happens inside one position, all the solutions stay trapped there too. Students miss the links and transition points between positions:

When you should abandon the arm drag because an opening for a leg entanglement has emerged

When it’s time to bail on the leg lock and wrestle up on top

When you’ve defended a leg lock safely, and an opportunity for a counter back take has opened up

Spending too long in specific positions creates knowledge that’s both narrow and fragile: it fades when time passes, and it doesn’t transfer when the position changes.

Why interleaving is the fix

Interleaving cycles you through multiple positions instead of trapping you in one. Patterns start to appear automatically: the same principle shows up in different contexts, so your brain connects them.

Instead of memorising techniques, you start seeing:

What never changes, and what does

Why it matters

And when to act on it

Interleaving turns jiu-jitsu from a list of moves into a set of patterns you can actually use under pressure. And, over time, you’re still cycling back enough to rack up enough training time in each position.

Part 3: Picking categories and themes for training

Let’s say you choose interleaving. The next question is: what do you interleave?

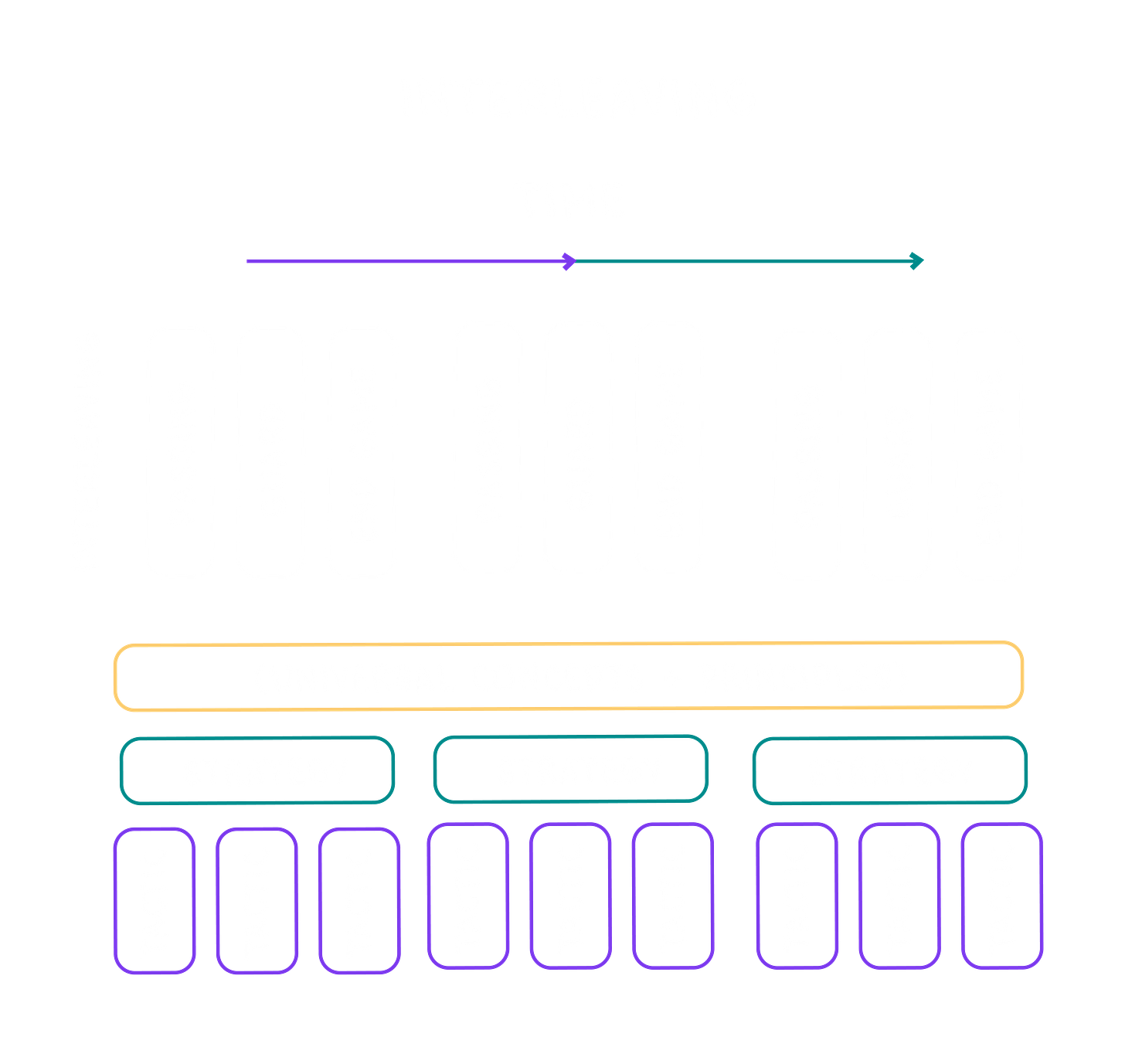

One of the hardest parts of BJJ is deciding where to spend your training time. So, to start simply, imagine you choose three broad categories:

Guard passing

Guard retention

End-game (dominant positions - finishes + defences)

Interleaving means you move between these categories more often - week to week instead of month to month. But that doesn’t mean your training becomes scattered. You can still have deeper themes running through everything you do.

Think of the categories as the where, and the themes as the what you’re actually learning. The positions change, but the principles repeat. Think of this as the subtext of every session: the deeper ideas you keep returning to, no matter where you are.

Here are three layers I’ve found work well, which I keep in mind no matter where I teach. They start with the principles that apply everywhere in jiu-jitsu, the things that don’t change, and end with the small, position-specific battles that do change.

1. Universal concepts and principles:

Think of principles in jiu-jitsu the way you think about the laws of physics. There aren’t many; they’re hard to break, and they explain almost everything.

The more you move between positions, the easier it becomes to teach these principles, because you can point to how they echo across the whole game.

For example, you can teach students to read:

Stance: how someone’s posture and structure dictate their attacks and defences.

The head–hip line: the invisible axis that tells you where their weight can go.

Flanking and planes: we can only attack and defend on certain angles. Protecting one exposes another.

Inside position/outside position: Entire games are built around controlling inside and outside space

By cycling through different positions, you keep reinforcing the same handful of universal rules. Over time, students learn not just techniques, but the physics of jiu-jitsu. Once they understand these laws, they can experiment with them confidently.

2. Strategy

If principles describe how jiu-jitsu works, strategy describes what you’re trying to achieve in a given position. It means students can trace every technique they're using back to a larger ‘why’.

This layer is more position-specific, but still broad. Good teaching focuses students on a clear aim:

What’s the main objective in this position?

What is your opponent trying to do in return?

How does that shape the choices on both sides?

When students train with strategic intent, they learn decision-making rather than just sequences. They understand not only what their options are, but also why specific options matter more than others for achieving a given goal.

3. Tactics

This is where most teaching happens by default: the specific techniques, grips, angles and mini-battles, just with the strategic context and principles removed.

Once the principles are clear and the strategy is defined, tactics finally make sense. This is where you can go deep into detail:

The exact grip that breaks the posture

The angle that turns a failed sweep into a back-take

The windows of opportunity you’re trying to create or shut down

How you execute all of the above under certain rulesets, and different time durations

Tactics become much more powerful when students already understand the principle they’re built on and the strategic purpose they serve.

Bringing it together

Interleaving gives you the schedule, the rhythm of changing positions often enough to keep patterns alive. Layering principles, strategy, and tactics into that schedule gives students something even better: a mix of things that change (the positions) and things that don’t (the underlying ideas).

That’s how you help them build a game that’s flexible, transferable, and built to last.

Thanks for reading!

We’re in spitting distance of 200 subscribers. I can’t thank you all enough for being here every week and reading my stuff. I hope you all have a fantastic weekend!