Deconstructing the ‘ecological’ approach

The 'eco' approach is an innovative way to sharpen our tactics but you should be cautious of any 'new' approach that comes with a glossary of terms

“Any intelligent fool can make things bigger and more complex... It takes a touch of genius --- and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction.”

Albert Einstein

Part 1: What the hell is the ‘ecological’ approach?

If you’ve been training at all over the last few months, you’ve likely heard murmurings, or excited preachings, of the ‘ecological’ approach.

The first time I heard about this approach was about six months ago when one of my students approached me after training to tell me they had gone ‘eco’. In a sport full of obsessives, my first reaction was that I was speaking to the frontman of another one of jiu-jitsu’s fanatical sub-crazes.

This became even more concerning when he started to rattle off a glossary of terms, each word sounding more confusing than the last—invariants, variability, terminal, continuous, pedagogy.

I was usually very good at keeping up with trends in the sport. Had I missed something?

But then, as his explanations and terminology became increasingly complex (all while not telling me exactly what the ecological approach actually was), my fear of missing out was quickly replaced by scepticism.

"Complexity is not to be avoided, but our reliance on it needs to be scrutinised. Too often, people hide behind complexity to mask their lack of understanding."

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

I spent the following months examining the ‘ecological approach’ and its terminology, aiming to strip the movement to its bare bones. I wanted to demystify the complexity created by its supporters and learn whether it was—or wasn’t—a new and innovative approach to training jiu-jitsu.

First, let’s lay out some general definitions of a traditional training approach vs an ecological training approach:

The Traditional Approach—The predominant training methodology in BJJ, this approach relies on grapplers repeatedly going over defined sequences of movement (drilling) to retain and use these sequences in live rounds (rolling).

The Ecological Approach - The approach targets learning through ‘game-based’ scenarios where the coach decides the rules of engagement. These ‘games’ are tailored to the principles or movements the coach would like their students to be able to implement in a live training scenario.

Immediately the ‘ecological’ approach seemed very appealing, especially when set against traditional forms of teaching. Anything which offers a different option from hours of drilling (and don’t even get me started on solo shrimping up and down the mat) seemed like a good approach on that basis alone.

However, when I began to deconstruct the ‘eco’ approach in isolation, I realised it had two distinct parts. One I loved, and the other I found deeply frustrating.

As a training methodology, the ‘ecological’ approach offers many new possibilities to sharpen tactical execution. Creating games that give either partner sets of goals while also adding constraints are both effective ways of channelling your student's focus into specific areas of the game and avoiding students being overwhelmed by complexity.

However, as coaching language, the words and terminology used to describe this approach seem purposefully complex. Not only does this blur the larger strategic ideas that underpin this methodology from students, but it is also difficult for those new to this type of training to learn exactly what it is.

While the training methodology is about using constraints to help students cut through the noise of mind-boggling complexity - the coaching language does the opposite. Instead of being equally clear and focused, the language of the eco approach (pushed by many of its promoters) contains an unbelievably complicated terminology repurposed from an adjacent scientific approach to repackage old jiu-jitsu ideas as new ones.

What the eco promoters communicate clearly

The ‘ecological’ approach is very good at describing what it isn’t.

Its promoters stand in clear opposition to linear teaching styles. It is not a conventional teaching approach where the professor goes through a sequence of techniques. It is not—and I repeat not—a fan of drilling for repetition.

While I am also against many of these things and again think there is value to the training approach, the more I deciphered the complex language, the more I think there is another motivator behind this movement that students should be wary of.

Part 2: New language, old ideas

Language is packaging

New language enables us to repackage old ideas and new ones. The more unfamiliar the terminology, the more a new student will think that the ideas behind the words are equally as novel. Also, you can’t sell a glossary of terms if you use language people are already familiar with.

While this wouldn’t be an issue if the new words described new ideas and concepts, I don’t think this is the case with the ecological approach. Many of the words seem to deliberately make fundamental, age-old principles of jiu-jitsu seem alien, especially when it comes to the larger, strategic ideas behind the approach.

Same strategy, new tactics

Before I dig into the deconstruction, I want to make the distinction between strategy and tactics absolutely clear.

Strategy - These are the big ideas and choices we have made to drive a certain training approach or teach a certain curriculum. This is where we decide exactly where we want to play and the fundamental principles we want our training to adopt. Examples of strategic choices in teaching can be something as big as which way around you believe position and submission should be prioritised or, on a smaller scale, your chosen game plan for a competition.

Tactics—These are the micro-steps we will take to execute our strategy over time. They always come downstream from strategy and are the minutiae that reflect the big strategic decisions and choices we made earlier on. If we chose to be a ‘position that leads to submission gym,’ then this should bleed into all of our training practices.

On a strategic level, when Greg Souders, one of the main promoters of the ecological approach, and John Danaher are asked what their fundamental aim in training athletes is, they both give a very similar response.

“We play the game of immobilisation as it leads to strangulation and breaking.”

Greg Souders

When asked the same question, here is John Danaher’s response.

“Jiu-jitsu is the art of control that leads to submission.”

John Danaher

For the rest of this post, I’ll look at how the ecological approach uses new terms to describe fundamental principles of a teaching strategy that pre-date the existence of the eco-movement.

On the strategic level, the ecological approach is built on the same fundamental principles brought forward by ‘systematic’ teachers like Danaher.

It is in the tactical realm of jiu-jitsu where I believe the ecological approach is at the forefront of training innovation. Game design offers coaches a new way to teach their students and help them channel their focus. A unique tactical execution of age-old ideas.

Direct attention - The fundamental idea behind the approach

The ‘ecological’ approach centres around the idea of ‘direct attention’. Within ecological psychology, this is the idea that individuals naturally and efficiently focus on elements of their environment that are directly relevant to their actions and needs, facilitated by their perceptual systems and the affordances present in the environment.

Now, even in that one sentence, there has already been an overwhelming amount of jargon. Let’s take these terms and narrow the scope to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.

Environment - In the context of BJJ, this would be live training. Some eco-enthusiasts refer to this as a ‘performance context’, which I think is again a complication for complication’s sake. The only thing a student needs to know is that when we roll and spar, BJJ is a complex and dynamic system.

Perceptual system—For jiu-jitsu athletes, this relates to the way in which our senses guide our decision-making under pressure. The problem is that if we work from sense alone, there’s no guarantee that our instincts are guiding us to make the right choices. For this, we need a certain level of guidance and focus. (We’ll get onto constraints and invariants shortly.)

Affordances: These are opportunities that a certain environment presents to an individual. In jiu-jitsu, the headquarters position would be a specific scenario that presents its own set of ‘affordances’. Although, again - I’d rather just refer to these as opportunities.

“The central goal is to take the athlete and put them back in the environment. Information, and what a coach gives is itself a constraint that guides students through this system.”

Greg Souders

The ecological approach tries to unify these three things so that athletes can spend the majority of their training time in live training scenarios. These come in the form of ‘constraint-led games’ which have athletes roll from specific positions with specific goals and objectives.

This helps channel focus while allowing athletes to spend the majority of their time in live-training scenarios or, in eco-language, the ‘environment’. By setting certain objectives, students can focus on certain segments (parts) of their game and identify the opportunities that are open to them. In an ideal scenario, students’ ability to identify these opportunities will become intuitive as their bodies naturally adapt to the demands of a complex system.

Linear vs Non-linear pedagogy - Sequential vs Systematic learning

The ecological approach is firmly in opposition to linear pedagogy and firmly in favour of non-linear pedagogy. The problem, of course, is that most people don’t know what these terms mean. Here is the best way to explain them in jiu-jitsu terms.

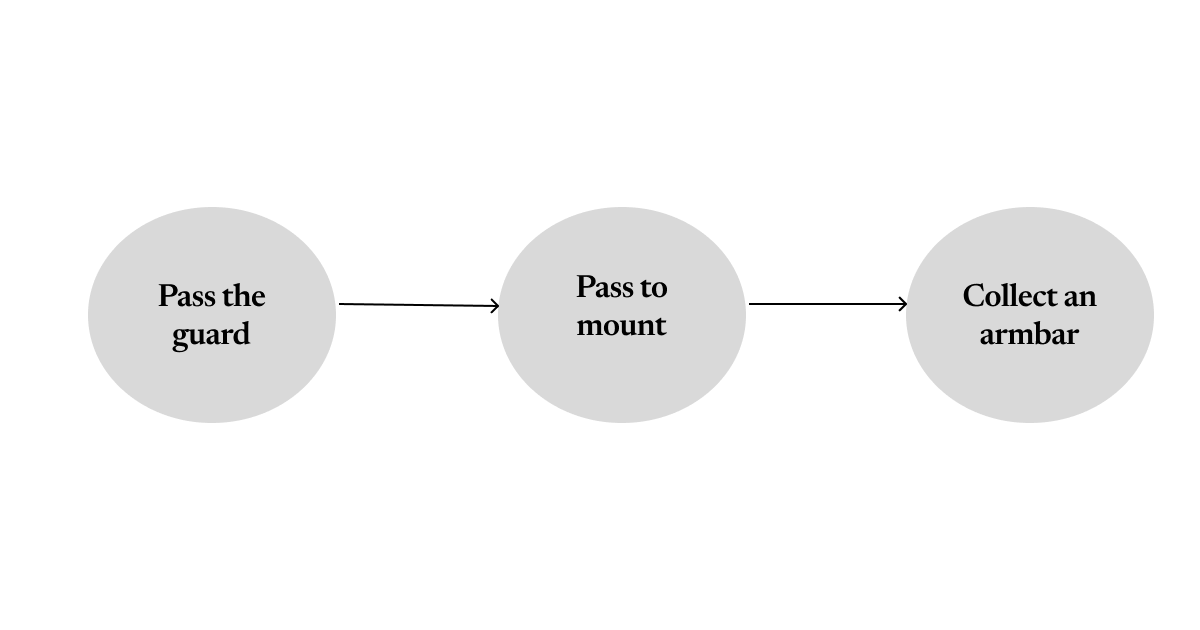

Linear pedagogy: This is when you’ve had a coach who teaches in sequences. For example, one drill could direct you to pass the guard > take side control > step into mount > and go for the armbar.

I share this complaint with ‘eco’ promoters. Most sequences work on the assumption that we are always guaranteed a similar response for each step in the progression. This is linear thinking. It looks like a nice path.

This is also referred to as sequential teaching.

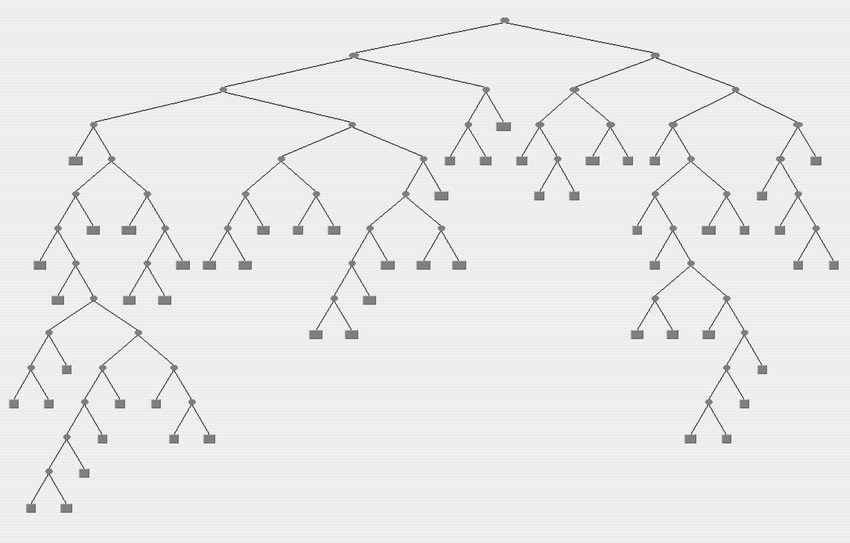

Non-linear pedagogy: This is when you accept that, for each step in the progression, you will face a new multitude of options, choices and threats simultaneously. This looks more like a decision tree:

When you think of jiu-jitsu like this, the sport takes on a different shape. Instead of one long path, there are constant intersections. Mastering jiu-jitsu is about learning how many choices are present to you at each step of progression and harnessing them so that they can be reshaped as dilemmas to use against your opponent.

Again, this fundamental approach is not unique to ecological training. This change in coaching emerged far earlier. John Danaher, in my eyes, had one of the biggest roles in promoting this more systematic view of jiu-jitsu.

Here’s a great short video of Lachlan Giles explaining these two different coaching approaches without the use of confusing terminology.

The constraints-led approach - training with a focus

The term ‘constraints-led approach’ is a much easier way to explain what the ‘ecological’ approach is and what it stands for.

If we look at live rolling or competition as the most ‘unconstrained approach’ where everything is on the table for both players - the ecological approach is about getting partners to drill with extremely specific objectives to channel their focus towards meaningful, but more micro goals.

But again, choosing our ‘constraints’ or the things our students can’t do is a decision that comes downstream from our teaching strategy. And one of the biggest strategic questions when it comes to teaching is: why ‘constrain’ at all?

Variability - The things that change

“The number of options that two players on a chess board can run through is astronomically high. There are 64 squares on a chessboard. The number of possible options is higher than the number of atoms in the known universe.”

John Danaher

*This quote and section were taken from a fascinating conversation between John Danaher and Lex Fridman. For the full conversation watch from 2:30:48 - ‘Superintelligent Robot vs Cyborg Gordon Ryan’.

Here, John Danaher describes the problem that faced a group of programmers in the 1980s. Their challenge was to create a computer that could beat a human at chess. The central problem, as Danaher describes above, is that if we break any game down option by option, there are unlimitless possibilities.

Danaher talks about how, as a coach, a similar problem emerges in ju-jitsu. If you are to teach the sport move by move, your students will be left overwhelmed by the number of options open to them.

To his credit, Souders highlights the same issue. What he refers to as the ‘novelty problem’ is the belief that students who are taught technique by technique will constantly be faced with attacks that seem completely new to them.

Variability is the term the ecological approach gives to this challenge. If something has a high variability, it means it is a scenario with lots of change, low variability is a scenario with less change. Constraints are used to control the level of variability so students aren’t overwhelmed.

But the issue still remains of the sheer magnitude of options open to us in jiu-jitsu. Thankfully, these programmers found the solution in the late 80s.

Invariants - General rules (the things that don’t change very often)

When we accept that no computer or human can process the number of options that jiu-jitsu presents, there needs to be a new route. The solution that the 80s programmers found and Danaher refers to is heuristics.

These, are ‘rules of thumb’ or as Danaher and many of his students refer to them during instructionals ‘general rules.’ In jiu-jitsu Danaher explains this could be something like ‘don’t turn your back to your opponent.’ There are exceptions to the rule, but in many scenarios it is good advice.

The power of a ‘heuristic’ is that once a student has it, a lot of options are ruled out. This helps narrow the scope of options for a student massively. Train jiu-jitsu for a decade, and say you’ve come up with ten time-tested heuristics. Danaher explains how this could cut down that initial astronomical set of options by a large amount.

Armed with the same insight, the programmers used heuristics to teach computer systems chess and eliminate the vast array of options that were possible. In the late 1990s, IBM’s computer Deep Blue beat Garry Kasparov in a landmark event between computer and man.

Invariants is just another term for heuristics or general rules. In situations where so much can change, invariants/heuristics are the things which don’t change very often.

It’s important to note that they exist on a macro and micro level. For example, generally speaking winning the inside space is a heuristic that is a good guiding principle across almost any position in jiu jitsu. But, within each position, there will be a more specific way to do this like getting chest to chest in halfguard.

Ecological coaches use these general rules in different ways to set goals for their students. Again, when building on tactics, this is a great way to reduce the vast array of options for students and help them focus their attention on the most pivotal variables. But just know: Before people called them invariants, there were called heuristics.

So is it just ‘positional’ sparring?

Both ‘postional’ or ‘specific sparring’ and ‘ecological games’ stem from a similar idea: addition by subtraction.

This is the idea that when you remove variables from a system, you don’t decrease the complexity. Instead, the complexity transfers to the remaining variables. Weird, I know.

To take a combat sport example, boxing has fewer variables than Muay Thai. One involves eight limbs, the other involves two. But that doesn’t mean boxing is any less complex.

Instead, the level of complexity transfers to the remaining variables. Watch any Thai Boxer spar with a professional boxer and you’ll see what I mean. This happens because, by removing variables the boxer can uncover more complexity within a smaller scope.

But there are meaningful differences when it comes to how these games are designed by a coach.

A positional round: A coach would start two players in a position like half guard, and usually give both a standard aim of passing (for the person on top) or sweeping (for the person on bottom).

An ecological game: Would be if two players started in half guard, with the bottom player trying solely to off-balance the top player for the whole round, while the top player tries to achieve some specific progression (chest to chest - getting behind the elbows - deflecting frames). The goals given are assymetric and meaningful.

Win conditions - Goals

The ecological approach is, therefore, positional-based training with much more specific and concrete goals for both players. This is a big strength of this style of approach in my eyes. Especially in the way that students can be given goals which run on different time horizons:

Continuous: A partner is given a task that lasts the entire round. This could be something like disrupting the position and disrupting control.

Terminal: A goal where they ‘win’ if they achieve it - for example achieving some sort of progression or submission. The round resets if they reach this.

Using these different types of goals can allow coaches to be much more prescriptive in the realm of tactics, which, again, is how we execute on a strategy over time. In my view, the focus in training not just on techniques, but how we execute them over time (depending on the time limit and ruleset) is woefully under-invested in by many coaches.

This is something I think the ecological approach can help be an antidote for.

Concrete use of language

The language used to objective-set, in contrast to the language used to describe ideas that underpin the approach, is extremely concrete and clear.

Coaches will find invariants and instead of talking in general positions will give concrete cues like ‘chest-to-chest’, ‘keep the far shoulder pinned’ etc.

This is where the eco approach is strongest. When it uses concrete language to emphasise certain goals so that students have tactical clarity.

It’s also important to note the use of these sorts of concrete cues have been used by Danaher and his offspring for years. Especially during instructionals, they often isolate very concrete goals in certain positions - they just don’t state them as invariants.

Part 3: Game design: A new approach to tactics that falls apart if it doesn’t come from sound strategy

Pros: Great for tactical nuance

I think the ecological approach, as a training methodology, is something which should be explored more to help students sharpen and refine their tactics. The things that make it unique from standard positional rounds are:

Specific goal setting, for control and submission

Goals that have partners play on different time horizons (continuous vs terminal) - i.e one partner playing a short game, while their opponent plays a long game. This can be absolutely pivotal to understand when honing tactics for certain rulesets.

Caveat 1: Game design must come downstream from sound strategy

Overall, I like the ecological approach as a means of sharpening tactics - but it MUST come downstream from sound strategy. Put simply, coaches who are designing the games MUST have a solid understanding of THE game.

Especially while the language used to describe the strategic logic behind eco training continues to be overly vague and complex - coaches taking this approach must understand that the only thing giving students an idea of the larger ideas behind jiu-jitsu will be the games.

Let’s hear from our good friend Sun Tzu one more time:

Learning from games only risks students ending up like Sun Tzu’s adversaries - quite aware of tactics, but unable to connect them to the larger ideas that they come from.

That’s why when it comes to game design, whether you call them heuristics, general rules, or invariants, a really strong strategic understanding of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is required to set them properly. If they are set by someone who is in-experienced, this can be dire for students.

Going back to those 80s programmers. Heuristics are only discovered as computers play billions and billions of chess games. Over the games, the general rules that are left over which are still correct most of the time become heuristics.

These options only become heuristics when they have stood the test of time after being tested over and over and over again.

A good heuristic/invariant can lead to a positive outcome in a vast range of scenarios. But, the same can be true in reverse. If someone inexperienced sets a bad heuristic/invariant, it can lead to a multitude of bad outcomes in many different scenarios.

Caveat 2: ‘Constraints’ should never come at the expense of teaching students to think in ‘dilemmas’

The ecological training methodology's fundamental strength is that it provides students with a focus amongst complexity. But if the games are set too focused and the objective too granular, there is a real danger they will become too linear.

For example, I watched an ecological game in which one person’s goal was to get to an opponent's back from the arm drag. When the game was set, the student doggedly pursued the arm drag but neglected much easier options in the process.

Despite their opponent changing leg position to block the back, which could have opened leg entries or other greater options, the student was left forcing a single move they should have abandoned earlier.

Don’t go too granular with the objective. This is hard, and again, this is why an experienced coach should design the game. Not enough constraints means overwhelming complexity, but too many create an unrealistic scenario—and ultimately, a linear approach.

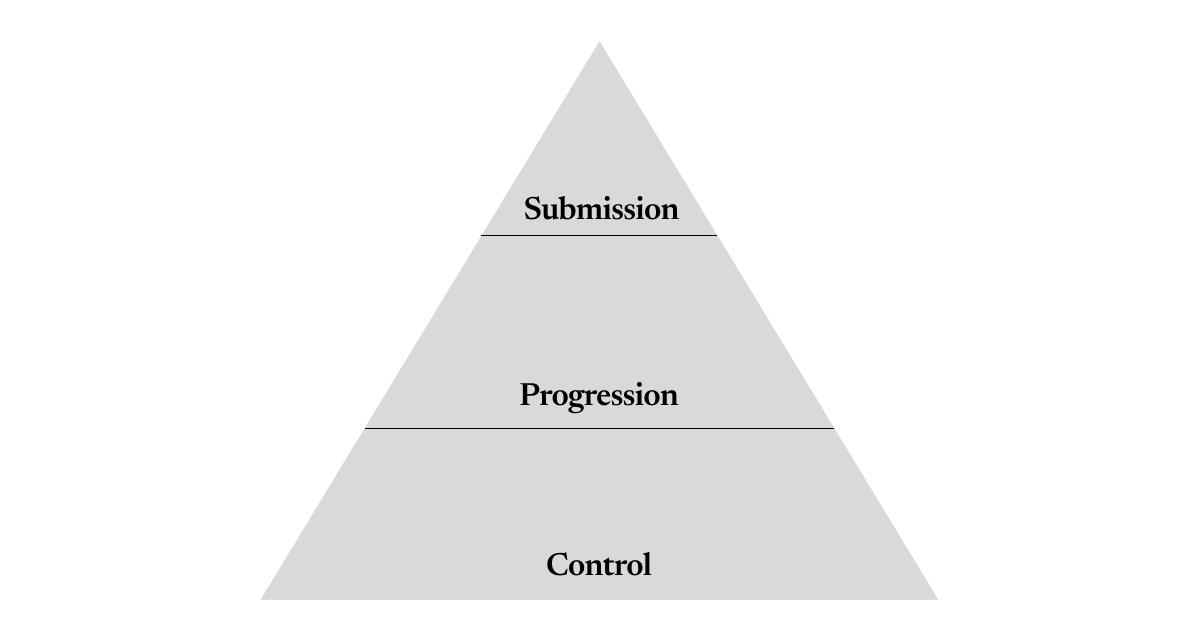

A basic pyramid to get started with game design

If you’ve read this far I hope you’ve enjoyed. As a reward, I’m offering you this incredibly simple pyramid to use as a guide to either creating your own eco games, or to tell your coach what you would like.

The triangle is organised in three layers. Each layer is reliant on the layer beneath it. If you follow the fundamental belief that both Souders and Danaher stated originally (basically control leads to submission) then this triangle should make sense.

Control is the foundation of everything we do in jiu-jitsu. Without control we cannot effectively progress, never mind submit. Progression is the next step up - with a strong base we can capitalise on opportunities that open up to us to upgrade our position.

Submission stands at the top of the pyramid. While there are some exceptions, if you have good control and positional progression - opportunities for submission should present themselves more and more.

Look at the pyramid and see where you are weakest. You can do this holistically, across your whole jiu-jitsu game or, for game-setting, go position by position. Once you find your weakness, creating a game will be easier.

As an example, if you’re struggling in the middle of the triangle in the half guard position - i.e you want to progress to a certain position but keep losing control -then design a game in which you give yourself a terminal goal like reaching chest to chest while your opponent has a continous goal of disrupting your position could be beneficial.

If anyone would like any more guidance on how to select invariants or design games - please let me know in the comments. I’d also love to hear your opinions on the ecological approach in general. Are you an eco promoter, a traditionalist or - like me - lost somewhere in between.

Until then, let me leave you with Nassim.

"The more complicated the rules and the model, the easier it is to game and exploit. Simplicity often forces clarity and honesty."

Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Interesting read, thanks

This was a wonderful article. It ties in perfectly with my recent approach of forgoing submissions for absolute control--pins, leg rides, etc. I don't know if I'd consider it 'eco', but it does get granular. And yes, being too granular has its drawbacks--the dogged determination to get the arm drag being a great example.