3 principles every high level guard passer should know

Why 'Prevent', 'Pressure' and 'Pin' are the holy trinity of guard passing concepts

If you’re looking for a granular breakdown of specific passes or techniques, you’ve come to the wrong place.

Not only would it have taken a lifetime to write, but even when it was finished it would not be of much use to you.

One of the biggest lessons jiu-jitsu has taught me is that if you want to go further faster, you should focus on overarching concepts, principles and magic ‘rules of thumb’ rather than spending the rest of eternity learning technique by technique.

That’s why today’s post is all about the concepts. I’ve been training for over ten years and have always leaned towards top position and passing. In this post, I’ll aim to compile endless hours on the mat, passing a huge variety of guards into what I call the 3 Ps.

The 3 Ps are a trifecta of guiding principles I give to my students, to help change their outlook and approach to passing the guard.

Each ‘P’ has been a landmark in my jiu-jitsu progression, but when combined together in the sequence I’ll explore today, they have led to emergent effects in my passing game that I could never have anticipated.

Let’s get into it.

Guard passing definition: In Brazilian Jiu Jitsu (BJJ), ‘guard passing’ refers to getting past your opponent’s legs (their guard) in order to reach dominant positions - most commonly - side control and mount.

Guard passing is a 3-step process

Before I even get into the 3 Ps, I always need to explain why it’s worth taking a segmented approach to guard passing in the first place.

Most students see guard passing as one single step—a homogenous mix of techniques that somehow get them from the tap-bump at the start of a roll to a dominant position.

This mentality is bad for a few reasons. Treating guard passing as a single step often means students wade blindly into dangerous waters. There has to be a step where they recognise the threat that their opponent’s guard poses, especially in an era where there are so many attacks available for the bottom player.

In turn, this can also lead to information overload in students, trying to think about how to defend, progress, pressure and pass all at the same time.

Having 3 stages allows a more advanced passing approach with each stage having its own distinct points of focus and objectives.

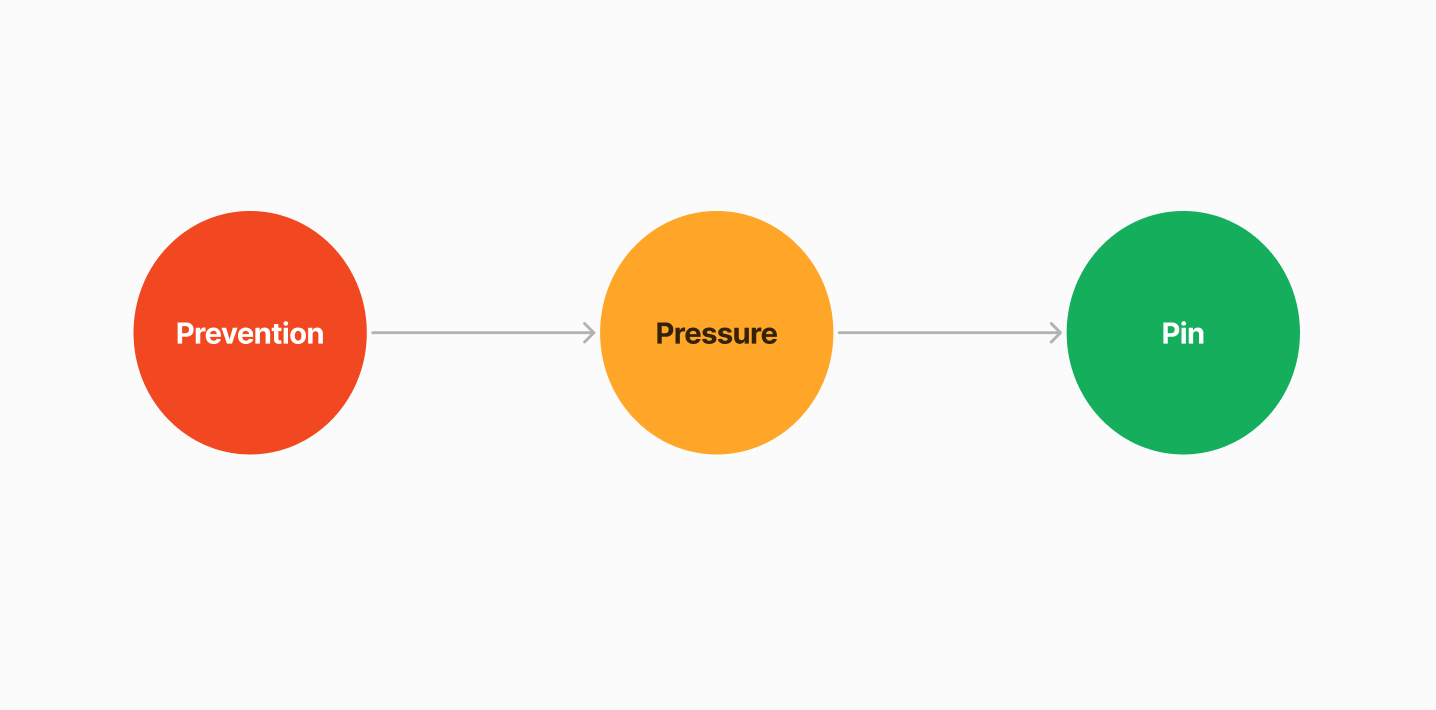

Here are the 3 Ps:

Prevent - point of focus - negating your opponents’ early attachments, creating openings to enter the ‘inside position’

Pressure - point of focus - once your opponent is in a mechanically weak position/ defensive cycle, apply pressure to increase your advantage over the course of the match

Pin - point of focus - finishing the pass, in which the sequence ends - or making a tactical retreat, in which we begin to cycle back through the 3 Ps.

Initially, I want my students to see passing like this (see below). Notice that as you move down the chain from ‘Prevention’, the risk that you’re exposed to decreases while your offensive opportunities increase. Hence the traffic light colouring.

1. Prevent

Taking the initiative

In chess, ‘taking the initiative’ is the name given to the concept that those who dictate the initial rules of engagement will have an inherent advantage over those who don’t. Like many good rules of thumb, this concept is prevalent across many fields and industries: ‘first mover advantage’ in business, ‘proactivity’ in psychology, and ‘offensive strategy’ in war.

Especially when passing, you have an inherent advantage: gravity.

On the most fundamental level, a guard passer’s job is to preserve this advantage and then progress to positions where they can leverage it against their opponent. But many guard passers lose this advantage early, often thinking of guard passing as one step and trying to skip to the ‘pin’.

This is exactly why I use the word prevent with my students. Even though it probably isn’t the first word that comes to mind when you think about taking the initiative, prevent helps my students narrow their focus to shutting down attacks while also being aware that it is in the early engagements when they are at the highest level of risk.

Once you understand the preventative nature of this step, you can become more proactive—shifting from reading openings to capitalising on them. Always consider that it is the ‘preventative’ skills that you develop here that will keep you in the game longer against higher belts, not necessarily the attacks.

Andrew Wiltse is an athlete with a style that embodies this principle. All of his passing is based on shutting down his opponent’s attachments and then capitalising on early engagements.

Here, he explains the basic idea behind his ‘buzzsaw’ approach, which shows just how aggressive the prevent stage can become once you become more aware of your opponent's attacks and how they can leave your opponent in overexposed positions. I’ve heard many interviews with Andrew in which he says that learning to break every single grip of an opponent during an early engagement was pivotal to increasing his success against higher belts in his early days of training, and for winning world titles later on.

Interestingly, out of the three stages, investing all of your time into this stage alone has the biggest impact on your short-term gains against higher belts.

The inside position should be your north star

In the prevent phase, we might be able to choose between an ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ approach when it comes to passing. But no matter which approach you start with, finding ways to control the ‘inside position’ should always be your ultimate goal.

If you skip ahead and don’t achieve the inside position, you won’t be able to use the mechanical advantage required to eliminate risk and add extra pressure.

Always remember, the moment you dominate the inside position, you pass the tipping point from a relatively equal exchange with your opponent, to having the offensive upper hand.

While you get deeper into an offensive cycle, your opponent will be forced into a defensive one. The whole ‘prevent’ phase should be dedicated to achieving this asymmetry.

The other reason ‘inside position’ is such a powerful concept is that it is more or less universal. Meaning in almost every position you attack in jiu-jitsu, from passing to leg locks, you are best to occupy the inside position.

There are exceptions to the rule, of course. But the fact these are ‘exceptions’ makes the inside position a powerful ‘rule’ to guide your whole passing process.

2. Pressure:

The middle step that everyone forgets

Once you’ve got your opponent in a defensive cycle, it’s vital to exploit your positional advantage. There are various ‘inside positions’ which are effective for passing including:

Headquarters (a personal favourite)

Chest to chest, knees to hip half guard

Various forms of ‘camping’ (a more recent approach)

There are, of course, many others. Whichever position you choose, you should measure its effictiveness on:

The ability it gives you to apply maximal pressure while exposing you to the minimum risk.

Why? In passing, you constantly face a trade-off of wanting to apply pressure to your opponent but leaving yourself overexposed in the process. Picking positions which eliminate your opponent’s ability to mount offence will keep you safe and allow you to drive even more pressure while using little to no energy.

Once you’ve got the balance, it is time to apply pressure.

Where strategy and tactics combine

Pressure is such an interesting part of passing because it should unite your match strategy (larger, long term aims, thinking of the match as a whole), and your tactics (how your executing on that second by second, minute by minute).

For example, pressure comes from positions where my opponent is at a positional disadvantage and has the primary benefit that in these positions, my opponent is expending more energy than me.

In the short-term (second to second, minute to minute) - this might open the door to a positional progression, pass or submission.

In the long-term (over the course of a whole match) - If I can maximise the amount of time I’m able to apply pressure (low energy expenditure for me, high energy for my opponent) this will lead to a massive pay off the deeper we get into the match. Everything further down the track, from passing finishes to our end game (submissions) will get easier.

Focusing on the long-term role that pressure plays becomes more important as you begin to face opponents with:

Better physical attributes

Higher skill level

I’d argue most of the matches at the highest level of jiu-jitsu come down to this tactic. The winner is often the one who can dictate the early engagement and then win the early offensive advantage. From there, pressure is the way they capitalise and build on this advantage so that they’re opponent cannot find a way back into the match.

Needless to say, any Gordan Ryan match in recent memory where he has prioritised half-guard passing on top follows this pattern. The more you improve your ability to recognise positions of mechanical weakness, the earlier you will be able to apply pressure in a match.

Athletes like Owen Jones and Gabriel Souza also understand this. Both use rapid side-to-side movement in the ‘prevent’ stage of their passing to force their opponent into high pummel positions by out-angling them. This allows them to force their opponent to use large amounts of energy just trying to retain the guard.

“The way I think of guard passing is: I want to make you retain, and then I’ll pass your guard retention.”

Owen Jones, from this episode of ‘Fix my game’

3. Pin

If you give the right attention and focus to the first Ps, the final P is almost a formality.

You will have controlled all the early engagements, applied all the pressure you can in the time your match allows, and likely will be dealing with an opponent with a sapped gas tank. Even then, it’s important to consider a few principles when you go for your finishing sequence.

Why? People’s ability to recover guard varies massively. If you have lazy guard passing finishes, you’ll constantly be in a ‘close but no cigar’ scenario when it comes to your passing. Also, when someone goes to recover their guard, the more advanced you become, you will be able to make a tactical decision whether to shut this down completely or to allow them to temporarily regain their guard. More on that in a moment.

Again the word choice is deliberate here.

Despite the fact that pin is usually used to describe the positions that follow your guard pass, I’ve found it a helpful word to help my students to focus on where to channel their pressure in the late stages of guard passing positions.

For example, in the late stages of a pass, you should already have gained controls that pin certain parts of your opponent’s body to the mat. It will be using these pins to create openings that will ensure you can finish the pass every time.

The golden rule of finishing guard passes

Again, the purpose of this post is not to get too granular on technical details. In short, in most late stages of guard passing you’ll have two parts of your opponents body pinned:

Upper body pin

Hip pin

When going for a guard-pass finish, choose which of the two you want to apply most of your pressure. This will depend on the type of pass and your opponent’s defence. Broadly speaking, the kryptonite to most guard passes is knee and elbow connection.

To combat this, most guard passing finishes play between a dilemma:

Widen the space: Here, you would use your pressure on your upper body and hip controls to widen the space between the knee and elbow. Think knee slice passes and dope mount passes. As a side note, I’ve found that focusing on ‘opening or preserving the space between knee and elbow’ is a great goal to give students during ecological rounds.

This video with Junny Ocasio shows perfectly how you can use your upper body and hip control to focus on widening the space between knee and elbow to finish the pass:

Accept the space is closed and pass to the back: There will always be positions where you cannot open this space, or perhaps do not have the necessary pinning controls to do so. A lot of the time, your opponent will have to commit themselves to one side in order to keep the space between their knee and elbow closed though. In this case, a much easier set of finishes will come from passing around to leg drag/ back take positions.

This ‘Knee cut to leg drag’ with Lachlan Giles and Levi Jones Leary is a fantastic example of this dilemma. Focus here on how Lachlan can maintain a tight knee and elbow connection but how Levi can capitalise on an advantage in angle that comes from this position.

But, the more you go through this sequence, the more you will begin to question whether it is always the best decision to pass immediately even when the position presents itself. Or whether there might be a better option…

To pass or not to pass - shifting from linear to non-linear

The more you get comfortable with the 3 Ps and complete the sequence over and over again you will eventually realise something counter intuitive. The more experienced your opponents are, and the more comfortable you become, you’ll need to start thinking more about what in chess is called a ‘tactical retreat’.

This is also a concept that exists in multiple fields: a ‘fallback position’ in a military context, ‘strategic withdrawal’ in business and economics or ‘defensive play’ in sports. All of these terms are about the idea that sometimes you need to take one step back to take three forward.

Let me explain.

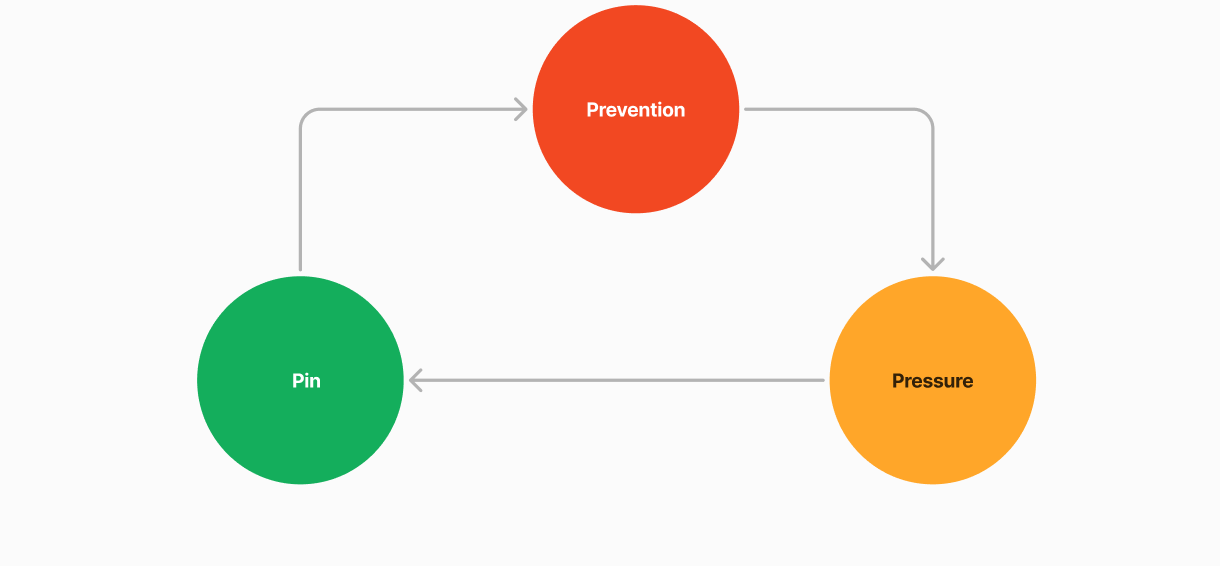

To start with, it’s good to think of the 3 Ps as a sequence. Not only does this give you a logical progression, but it also ensures you have the right focus for different stages of the match. But the more advanced you become, there’s a danger you start to think of jiu-jitsu in terms that are too linear.

Of course, there are times you have a match where you go through the 3 Ps and submit your opponent. But against any reasonable opposition, you should work on the assumption that it won’t be this easy.

This is when you need to start thinking of the 3 Ps less as a sequence, and more as a loop or a cycle. The steps will still follow from one another, but especially in the ‘pin’ stage there will be scenarios where it makes more sense to let your opponent reguard.

Why? It’s counterintuitive, but often, your opponent will expend much more energy trying to prevent your pass from a mechanically weak position than they will underneath side control or mount. Granted, mount especially has become a much more proactive position in recent years.

At these moments, you will also have a choice to either channel all of your energy into holding the position at all costs (which comes at an energy cost to you) or, allow your opponent to retain their guard while applying, or simply by allowing them to carry your weight, to make their recovery more difficult.

This approach comes at no energy cost to you and at a much higher energy cost for your opponent. It’s tempting to think that passing works in one direction: forward. But great passers realise that passing is multi-directional.

Sometimes, learning how to go through the 3 Ps in reverse is what will tire our opponent the most, allowing more passes (if you’re competing with points) and easier submissions.

Learning this principle and how the 3 Ps link together is by far one of the biggest developments I’ve experienced with my own passing in previous years. I hope it has the same impact on your passing. I’d love to hear in the comments if there are any passing principles which you feel have really advanced your game, or if you have a specific topic, position or area of jiu-jitsu you’d like to read more about.

Thanks for reading!

If you found this read useful and think you have a training partner that would benefit, please share my substack with them. All my posts in some way will try and compile lessons that took me over a decade to learn in relatively short reads!

This is a great article. I've been having a lot of success with the camping/high-leg passing that Gordon has been using--especially the high-leg where you post on far shin and far shoulder and end up in their North-South. Leg drags have also been a great option for opponents who are stingy with the elbow-knee space. From their I can go to honeyhole, tight-waist pass, or back take.